Politics

Petro-politics: Making sense of PM Imran’s ‘gift’ to the people

Petro-politics: Making sense of PM Imran’s ‘gift’ to the people

Published

4 years agoon

By

wajahat

The relief package marks a clear shift from the fiscal reforms agenda, which may not only irk the IMF but also hurt the economy.

Prime Minister Imran Khan caught almost everyone by surprise on Monday. Amid a global crisis in the form of the Russian invasion of Ukraine that sent global markets tumbling and a political storm brewing at home, the premier announced a major cut of Rs10 in the prices of petroleum products — the single largest contributor to the country’s import bill.

The move, which left citizens stunned and economists scratching their heads, was not just limited to subsidising petroleum products.

No, the prime minister went ahead and slashed energy prices, announced tax exemptions for IT companies and freelancers associated with the sector, exemptions from capital gains tax for IT startups, skills-based internships for graduates and an increase in the stipend disbursed under the Ehsaas programme from Rs12,000 to Rs14,000. Moreover, the cut in energy and fuel prices would be sustained for the next three to four months till the next budget, he promised.

Needless to say, the move raised many an eyebrow — and for good measure too.

Where would the government get the fiscal space to cover the expenditures, pundits questioned. Had it not increased petrol prices by Rs12 just a couple of weeks ago, saying it could not afford to offer subsidies? Are these measures sustainable? What about Pakistan’s commitments to the IMF? More importantly, how would the move impact Pakistan’s economy in the long term?

Let’s try to address these questions one at a time.

A Populist move. Period.

The move, though unexpected, is not a new trick in Pakistan’s political landscape, where almost every government has attempted to check petrol prices as a shortcut to wooing the electorate every time it found itself in trouble.

In this case, however, it is all the more difficult to see economic sense in the move as the government had raised petrol prices by Rs12 just a couple of weeks ago, when the benchmark crude oil was trading at around $95 per barrel. Nothing has changed since, except that the same commodity is being traded today at $110 per barrel.

The only logical explanation one can hence arrive at is this: that the announcement is a purely populist move, designed to buy the government some political mileage as opposition parties up the ante of an impending no-confidence vote and embark on long marches.

Perhaps the biggest giveaway in this case is the timing of the move — the pressure being built up by the opposition — and perhaps the government’s own allies — combined with an increasingly restless electorate seem to have forced the government to take this route.

The saddest part is that the very people, in whose name these actions are being taken, will see little to no benefit of the reduced prices, except that they may pay slightly lower amounts for getting their vehicles’ tanks filled. The cut will not inflict any substantial dent to inflation in the medium to long term.

Petroleum and energy prices, though important, are just one contributor to inflation in Pakistan. There are many other factors, such as governance or lack thereof, supply chain issues and hoarding, which have broken the backs of the most vulnerable for the past several years.

Moreover, once the prices of commodities go up, they are hardly ever seen to drop with a cut in petrol prices — at least not by any significant measure. For example, how many times have you seen a major cut in bus fares or product prices, even when the prices of petroleum products have been decreased? In fact, rarely is the benefit of a decrease in commodity prices passed on to the end consumer.

What the public will undoubtedly feel, however, is the pinch of inflationary pressures on commodity prices as a result of the fiscal deficit created by these populist measures. The government’s own estimates to finance this cut seem to ignore the rising trend of crude oil prices and their impact over the next three to four months. Freezing the prices at the current level till the next budget at a time when global oil prices are on an exceptional surge will leave an unbearable dent on the fiscal deficit.

The IMF conundrum

While the cut in petrol and energy prices were immediately implemented, the other measures announced by the prime minister in his address may take more time or may not even see the light of day until after the next budget. The process of designing and implementing these reforms — other than Ehsaas transfers — may take another two to three months, when it is time for the next budget. The announcement, however, will be enough to create some goodwill on its face value and buy the government some time.

And while it may yet be able to finance the cut in petrol prices — estimated at approximately Rs60 billion for the next four months — it would be hard put to both find the resources to implement the other measures and also explain its position to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which finally released the sixth $1 billion tranche under its Extended Fund Facility after months of deliberations and only after Pakistan agreed to some very tough conditions, including the mini-budget.

While there are reports that the government is hoping to finance this Rs250-300 billion package from cuts in expenditure, and not by borrowing, one is hard-pressed to understand why these possible avenues were not utilised when the mini-budget was presented. What has changed that these avenues are suddenly now available?

If indeed the government does push on for the implementation of all the measures announced by the premier, it would not only be reneging on its commitments to the IMF, specifically in relation to fiscal reforms and pricing in the energy sector, but also jeopardising the seventh review by the Fund.

Not only will this hurt the government’s credibility, any form of derailment from the IMF programme will have an adverse effect on the exchange rate as well as the foreign exchange reserves, further elevating the inflationary pressure. This in turn can have wide ranging medium to long term consequences for the economy. The market is already exhibiting fears around this scenario.

Moreover, if the government does go ahead with the measures, it will also hurt its standing with other development partners such as the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, who may stop their support in light of the country’s reversal on its reforms agenda. We had, in fact, seen a glimpse of this last year as the IMF was conducting the sixth review, when all other development partners were waiting for it to finish before extending support.

What is most unfortunate in this whole scenario is that despite the months of pain and suffering, taking tough decisions that caused the economy to contract even before Covid-19 struck and introducing a tough mini-budget, Pakistan would not be able to complete its reforms agenda simply because politics trumped basic economic sense.

You may like

-

Supreme Court annuls trials of civilians in military courts

-

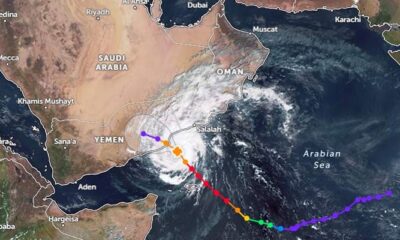

Sea conditions ‘very high’ as Cyclone Tej moves towards northwestward

-

IMF condition: ECC set to green light gas tariff hike today

-

UN experts claim Israeli actions in Gaza ‘violation of international humanitarian law’

-

Arshad Sharif’s wife files lawsuit against Kenyan police over journalist’s killing

-

World Cup 2023: Pakistan opt to bowl first against Australia after winning toss

In a unanimous verdict, a five-member bench of the Supreme Court on Monday declared civilians’ trials in military courts null and void as it admitted the petitions challenging the trial of civilians involved in the May 9 riots triggered by the arrest of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) chief Imran Khan in a corruption case.

The five-member apex court bench — headed by Justice Ijaz Ul Ahsan, and comprising Justice Munib Akhtar, Justice Yahya Afridi, Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi and Justice Ayesha Malik — heard the petitions filed by the PTI chief and others on Monday.

The larger bench in its short verdict ordered that 102 accused arrested under the Army Act be tried in the criminal court and ruled that the trial of any civilian if held in military court has been declared null and void.

The apex court had reserved the verdict earlier today after Attorney General of Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Usman Awan completed his arguments centred around the domain and scope of the military courts to try the civilians under the Army Act.

At the outset of the hearing today, petitioner lawyer Salman Akram Raja told the bench that trials of civilians already commenced before the top court’s verdict in the matter.

Responding to this, Justice Ahsan said the method of conducting proceedings of the case would be settled after Attorney General of Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Usman Awan completed his arguments.

Presenting his arguments, the AGP said he would explain to the court why a constitutional amendment was necessary to form military courts in 2015 to try the terrorists.

Responding to Justice Ahsan’s query, AGP Awan said the accused who were tried in military courts were local as well as foreign nationals.

He said the accused would be tried under Section 2 (1) (D) of the Official Secrets Act and a trial under the Army Act would fulfill all the requirements of a criminal case.

“The trial of the May 9 accused will be held in line with the procedure of a criminal court,” the AGP said.

The AGP said the 21st Amendment was passed because the terrorists did not fall in the ambit of the Army Act.

“Amendment was necessary for the trial of terrorists [then] why amendment not required for the civilians? At the time of the 21st constitutional amendment, did the accused attack the army or installations?” inquired Justice Ahsan.

AGP Awan replied that the 21st Amendment included a provision to try accused involved in attacking restricted areas.

“How do civilians come under the ambit of the Army Act?” Justice Ahsan asked the AGP.

Justice Malik asked AGP Awan to explain what does Article 8 of the Constitution say. “According to Article 8, legislation against fundamental rights cannot be sustained,” the AGP responded.

Justice Malik observed that the Army Act was enacted to establish discipline in the forces. “How can the law of discipline in the armed forces be applied to civilians?” she inquired.

The AGP responded by saying that discipline of the forces is an internal matter while obstructing armed forces from discharging duties is a separate issue.

He said any person facing the charges under the Army Act can be tried in military courts.

“The laws you [AGP] are referring to are related to army discipline,” Justice Ahsan said.

Justice Malik inquired whether the provision of fundamental rights be left to the will of Parliament.

“The Constitution ensures the provision of fundamental rights at all costs,” she added.

If the court opened this door then even a traffic signal violator will be deprived of his fundamental rights, Justice Malik said.

The AGP told the bench that court-martial is not an established court under Article 175 of the Constitution.

At which, Justice Ahsan said court martials are not under Article 175 but are courts established under the Constitution and Law.

After hearing the arguments, the bench reserved the verdict on the petitions.

A day earlier, the federal government informed the apex court that the military trials of civilians had already commenced.

After concluding the hearing, Justice Ahsan hinted at issuing a short order on the petitions.

The government told the court about the development related to trials in the military court in a miscellaneous application following orders of the top court on August 3, highlighting that at least 102 people were taken into custody due to their involvement in the attacks on military installations and establishments.

Suspects express confidence in mly courts

The same day, expressing their “faith and confidence” in military authorities, nine of the May 9 suspects — who are currently in army’s custody — moved the Supreme Court, seeking an order for their trial in the military court be proceeded and concluded expeditiously to “meet the ends of justice”.

Nine out of more than 100 suspects, who were in the army’s custody, filed their petitions in the apex court via an advocate-on-record.

The May 9 riots were triggered almost across the country after former prime minister Imran Khan’s — who was removed from office via a vote of no confidence in April last year — arrest in the £190 million settlement case. Hundreds of PTI workers and senior leaders were put behind bars for their involvement in violence and attacks on military installations.

Last hearing

In response to the move by the then-government and military to try the May 9 protestors in military courts, PTI Chairman Imran Khan, former chief justice Jawwad S Khawaja, lawyer Aitzaz Ahsan, and five civil society members, including Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (Piler) Executive Director Karamat Ali, requested the apex court to declare the military trials “unconstitutional”.

The initial hearings were marred by objections on the bench formation and recusals by the judges. Eventually, the six-member bench heard the petitions.

However, in the last hearing on August 3, the then-chief justice Umar Ata Bandial said the apex court would stop the country’s army from resorting to any unconstitutional moves while hearing the pleas challenging the trial of civilians in military courts.

A six-member bench, led by the CJP and comprising Justice Ijaz Ul Ahsan, Justice Munib Akhtar, Justice Yahya Afridi, Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi, and Justice Ayesha Malik, heard the case.

In the last hearing, the case was adjourned indefinitely after the Attorney General for Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Usman Awan assured the then CJP that the military trials would not proceed without informing the apex court.

Politics

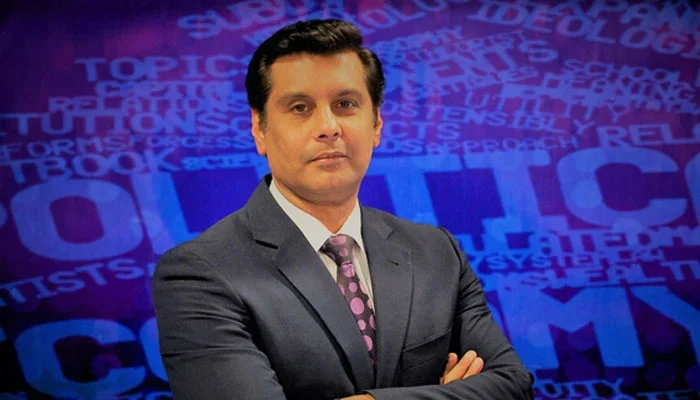

Arshad Sharif’s wife files lawsuit against Kenyan police over journalist’s killing

Published

2 years agoon

By

- Javeria Siddique filed lawsuit to “get justice for her husband”.

- Lawsuit also seeks “public apology” from Kenyan attorney general.

- Journalist was shot dead in October 2022 by Kenyan police officers.

NAIROBI: Slain journalist Arshad Sharif’s wife has registered a case against the Kenyan Elite police unit for her husband’s murder in Kenya, reported The News.

Javeria Siddique in her petition has made the attorney general of Kenya, national police service of the country and the director public prosecution respondents.

She has urged that the officers involved in Sharif’s murder be put on trial and be punished for their crime.

She urged the court to issue directives to the Kenyan attorney general (AG) to apologise to Sharif’s family within seven days of court’s orders, admit facts, accept responsibility and issue a written apology at public level.

Sharif’s widow, while confirming the filing of the case, said: “I have got a case registered in Nairobi for seeking justice in murder case of my husband. We got the case registered against general service unit of Kenya because they committed crime publicly and then admitted it was matter of mistaken identity. But to me it was targeted murder. But Kenyan government never apologised. They never contacted us.”

The registration of the case comes after it was reported the five Kenyan police officers who were involved in the killing quietly resumed their duties without any action taken against them.

Nine months after the killing of the journalist at a roadblock in a remote part of the East African country, the five police officers involved in the brutal killing are enjoying full police perks and their suspensions have turned out to be only a whitewash by the Kenyan authorities.

A trusted security source revealed that the five cops involved in the fatal shootout are back to work and two of them have been promoted to senior ranks.

Kenya’s Independent Policing and Oversight Authority (IPOA), the body that is tasked with investigating the conduct of police officers, despite making a promise to give an update on Sharif’s murder within weeks has not made its findings public in over nine months.

Sharif had arrived in the Kenyan capital on August 20 and died on October 23 last year in a shootout in which his driver Khurram Ahmad survived miraculously.

The 49-year-old had fled Pakistan in August to avoid arrest after he was slapped with several cases including sedition charges over an interview with Shahbaz Gill, a former aide of Imran Khan.

After reaching Kenya’s capital Nairobi, Sharif stayed at the Riverside penthouse of businessman Waqar Ahmad who is also Khurram’s brother who was driving him when he was killed.

The journalist was being driven from Ammodump Kwenia training camp, a joint which is owned by Waqar and they were heading to Nairobi County where he was staying.

- ECP notice on inter-party elections “serious mistake,” says PTI.

- ECP has no justification for depriving PTI of symbol: Senator Zafar.

- 41 days passed but detailed decision not issued yet: PTI’s counsel.

ISLAMABAD: The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) has urged the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) to issue its verbal order regarding issuance of election symbol and reminded the electoral body of its constitutional duty to hold free and fair elections in the country, The News reported on Thursday.

Senator Barrister Syed Ali Zafar, the party’s counsel, on Wednesday filed an application with the Election Commission requesting for issuance of a detailed written order in the interest of justice and fairness.

The party has urged the Election Commission to issue a detailed decision without delay in light of its announcement concerning issuance of election symbols.

According to Senator Zafar, the Election Commission had issued a notice to the PTI for refusing to issue the symbol of “bat” on the basis of intra-party elections.

He insisted the commission’s notice on the basis of inter-party elections was a serious mistake, as the PTI had held intra-party elections on June 9, 2022 as per its constitution.

He maintained that the ECP had no justification of depriving the PTI of its symbol after holding the intra-party elections, as the electoral body had never objected to the intra-party elections but identified some defects in the submitted document, which had been removed.

The Election Commission in its August 30, 2023 decision, he pointed out, accepted the PTI’s decision to hold the intra-party elections and announced the decision to issue the election symbol of “bat” and after the August 30 decision of the Election Commission, the matter had become final and complete.

He recalled that at the time of the verbal announcement of the August 30 decision, the Election Commission announced to issue a detailed decision in this regard and this was widely highlighted in print, electronic and social media.

However, he noted, 41 days had passed since the August 30 decision, but a detailed decision had not yet been provided.

“PTI is the largest political party in the country, which is contesting the upcoming elections. Not issuing a detailed decision even after 41 days is a clear violation of fundamental rights, including articles 4, 9, 10A, 15, 16, 17 and 26 of the Constitution,” he said.

Ali Zafar insisted that according to the Constitution, the Election Commission was bound to hold free, fair, impartial and transparent elections, while avoiding detailed decisions was a deviation from this constitutional mandate.

Supreme Court annuls trials of civilians in military courts

Sea conditions ‘very high’ as Cyclone Tej moves towards northwestward

IMF condition: ECC set to green light gas tariff hike today

Barwaan Khiladi: Kinza Hashmi discusses her role as Alia

Snap launches tools for parents to monitor teens’ contacts

WATCH: Pakistani traveller deported from Dubai for damaging plane mid-air

Learn First | How to Create Amazon Seller Account in Pakistan – Step by Step

Sajjad Jani Funny Mushaira | Funny Poetry On Cars🚗 | Funny Videos | Sajjad Jani Official Team