Tech

Study reveals how an ancient beast failed to survive millions of years ago

Published

3 years agoon

By

In a new revelation about the extinction of species from the earth roughly 252 million years ago, scientists said that the fossils excavated in South Africa provide insight into predators that over multiple generations migrated halfway around the world and ultimately failed to survive, reported Reuters.

It is believed that the mass extinction occurred due to global warming started after calamitous volcanism in Siberia and dooming perhaps 90% of species.

The extinction event that occurred even before the wiping out of dinosaurs — 66 million years ago — remained there for a longer time with species perishing one by one as conditions worsened.

This beast, a tiger-sized, sabre-toothed mammal forerunner called Inostrancevia, had been known only from fossils unearthed in Russia’s northwestern corner bordering the Arctic Sea until new remains were discovered at a farm in central South Africa.

The research reveals that “the new fossils suggest that Inostrancevia left its place of origin and trekked over time — maybe hundreds or thousands of years — about 7,000 miles across Earth’s ancient supercontinent Pangaea at a time when today’s continents were united.”

The findings of the research were published in the journal Current Biology.

The researchers noted that “Inostrancevia filled the ecological niche of a top predator in South Africa left vacant after four other species already had vanished.”

Paleontologist Christian Kammerer of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and the lead author of the study said: “However, it did not survive long. Inostrancevia and all of its closest relatives disappeared in the mass extinction called the Great Dying.”

“So, they have no living descendants, but they are a member of the larger group called synapsids, which includes mammals as living representatives,” Kammerer added.

Inostrancevia is part of a collection of animals called protomammals that combine reptile-like and mammal-like features.

The research estimated that it was 10-13 feet (3-4 meters) long, roughly the size of a Siberian tiger, but with a proportionally larger and elongated skull as well as enormous, blade-like canine teeth.

“I suspect these animals primarily killed prey with their sabre-like canine fangs and either carved out chunks of meat with the serrated incisors or, if it was small enough, swallowed the prey whole,” Kammerer said.

“Inostrancevia’s body had an unusual posture typical of protomammals, not quite sprawling like a reptile or erect like a mammal but something in between, with sprawled forelimbs and mostly erect hind limbs. It also lacked the mammalian facial musculature and would not have produced milk,” according to the scientists.

“Whether these animals were furry or not remains an open question,” Kammerer said.

“They tend to take a relatively long time to mature and have few offspring. When ecosystems are disrupted and prey supplies are reduced or available habitat is limited, top predators are disproportionately affected,” Kammerer said.

The researchers see similar conditions between the Permian crisis and today’s human-induced climate change.

“The hardship these species faced was a direct result of a global-warming climate crisis, so they really had no choice but to adapt to it or go extinct. This is clear by evidence of their brief perseverance in spite of these conditions, but eventually, they disappeared one by one,” said palaeontologist and study co-author Pia Viglietti of the Field Museum in Chicago.

“Unlike our Permian predecessors,” Viglietti added, “we actually have the ability to do something to prevent this kind of ecosystem crisis from happening again.”

You may like

-

‘DREAM FOR CHEATERS’: WhatsApp’s rolls out new feature to change the game

-

Instagrammers decry Meta shadowbanning pro-Palestinian content

-

Meta to limit ‘unwelcome comments’ on Facebook posts about Israel-Gaza war

-

IT minister underscores SIFC initiatives to revolutionise IT, telecom in Pakistan

-

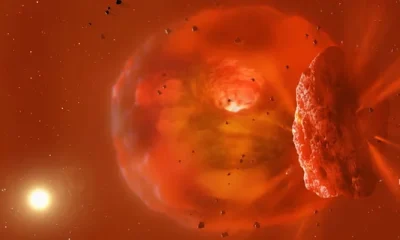

Spectacular: Scientists find two icy giants colliding in deep space

-

Is Starlink satellite threat to humans? Elon Musk SpaceX breaks silence

In a unanimous verdict, a five-member bench of the Supreme Court on Monday declared civilians’ trials in military courts null and void as it admitted the petitions challenging the trial of civilians involved in the May 9 riots triggered by the arrest of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) chief Imran Khan in a corruption case.

The five-member apex court bench — headed by Justice Ijaz Ul Ahsan, and comprising Justice Munib Akhtar, Justice Yahya Afridi, Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi and Justice Ayesha Malik — heard the petitions filed by the PTI chief and others on Monday.

The larger bench in its short verdict ordered that 102 accused arrested under the Army Act be tried in the criminal court and ruled that the trial of any civilian if held in military court has been declared null and void.

The apex court had reserved the verdict earlier today after Attorney General of Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Usman Awan completed his arguments centred around the domain and scope of the military courts to try the civilians under the Army Act.

At the outset of the hearing today, petitioner lawyer Salman Akram Raja told the bench that trials of civilians already commenced before the top court’s verdict in the matter.

Responding to this, Justice Ahsan said the method of conducting proceedings of the case would be settled after Attorney General of Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Usman Awan completed his arguments.

Presenting his arguments, the AGP said he would explain to the court why a constitutional amendment was necessary to form military courts in 2015 to try the terrorists.

Responding to Justice Ahsan’s query, AGP Awan said the accused who were tried in military courts were local as well as foreign nationals.

He said the accused would be tried under Section 2 (1) (D) of the Official Secrets Act and a trial under the Army Act would fulfill all the requirements of a criminal case.

“The trial of the May 9 accused will be held in line with the procedure of a criminal court,” the AGP said.

The AGP said the 21st Amendment was passed because the terrorists did not fall in the ambit of the Army Act.

“Amendment was necessary for the trial of terrorists [then] why amendment not required for the civilians? At the time of the 21st constitutional amendment, did the accused attack the army or installations?” inquired Justice Ahsan.

AGP Awan replied that the 21st Amendment included a provision to try accused involved in attacking restricted areas.

“How do civilians come under the ambit of the Army Act?” Justice Ahsan asked the AGP.

Justice Malik asked AGP Awan to explain what does Article 8 of the Constitution say. “According to Article 8, legislation against fundamental rights cannot be sustained,” the AGP responded.

Justice Malik observed that the Army Act was enacted to establish discipline in the forces. “How can the law of discipline in the armed forces be applied to civilians?” she inquired.

The AGP responded by saying that discipline of the forces is an internal matter while obstructing armed forces from discharging duties is a separate issue.

He said any person facing the charges under the Army Act can be tried in military courts.

“The laws you [AGP] are referring to are related to army discipline,” Justice Ahsan said.

Justice Malik inquired whether the provision of fundamental rights be left to the will of Parliament.

“The Constitution ensures the provision of fundamental rights at all costs,” she added.

If the court opened this door then even a traffic signal violator will be deprived of his fundamental rights, Justice Malik said.

The AGP told the bench that court-martial is not an established court under Article 175 of the Constitution.

At which, Justice Ahsan said court martials are not under Article 175 but are courts established under the Constitution and Law.

After hearing the arguments, the bench reserved the verdict on the petitions.

A day earlier, the federal government informed the apex court that the military trials of civilians had already commenced.

After concluding the hearing, Justice Ahsan hinted at issuing a short order on the petitions.

The government told the court about the development related to trials in the military court in a miscellaneous application following orders of the top court on August 3, highlighting that at least 102 people were taken into custody due to their involvement in the attacks on military installations and establishments.

Suspects express confidence in mly courts

The same day, expressing their “faith and confidence” in military authorities, nine of the May 9 suspects — who are currently in army’s custody — moved the Supreme Court, seeking an order for their trial in the military court be proceeded and concluded expeditiously to “meet the ends of justice”.

Nine out of more than 100 suspects, who were in the army’s custody, filed their petitions in the apex court via an advocate-on-record.

The May 9 riots were triggered almost across the country after former prime minister Imran Khan’s — who was removed from office via a vote of no confidence in April last year — arrest in the £190 million settlement case. Hundreds of PTI workers and senior leaders were put behind bars for their involvement in violence and attacks on military installations.

Last hearing

In response to the move by the then-government and military to try the May 9 protestors in military courts, PTI Chairman Imran Khan, former chief justice Jawwad S Khawaja, lawyer Aitzaz Ahsan, and five civil society members, including Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (Piler) Executive Director Karamat Ali, requested the apex court to declare the military trials “unconstitutional”.

The initial hearings were marred by objections on the bench formation and recusals by the judges. Eventually, the six-member bench heard the petitions.

However, in the last hearing on August 3, the then-chief justice Umar Ata Bandial said the apex court would stop the country’s army from resorting to any unconstitutional moves while hearing the pleas challenging the trial of civilians in military courts.

A six-member bench, led by the CJP and comprising Justice Ijaz Ul Ahsan, Justice Munib Akhtar, Justice Yahya Afridi, Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi, and Justice Ayesha Malik, heard the case.

In the last hearing, the case was adjourned indefinitely after the Attorney General for Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Usman Awan assured the then CJP that the military trials would not proceed without informing the apex court.

Tech

‘DREAM FOR CHEATERS’: WhatsApp’s rolls out new feature to change the game

Published

2 years agoon

By

WhatsApp has introduced a significant change that allows users to have two accounts on the same phone, a feature that has been highly requested for years.

While this change is aimed at simplifying the user experience for those who have both personal and work phones, there are concerns that it could facilitate dishonesty in relationships.

Mark Zuckerberg, the owner of WhatsApp, announced this development, ending the inconvenience of logging in and out or carrying two separate phones.

To use this feature, a smartphone must be capable of accepting more than one SIM card or an eSIM, which allows two phone numbers to run from a single device without physical SIM cards. eSIMs are added virtually to the handset by network providers who support this technology.

For travellers, eSIMs offer flexibility as they can obtain a second SIM plan from a local provider, avoiding the high costs of using their main SIM abroad or the need to purchase a new SIM upon arrival. However, eSIM technology is not widely known among consumers.

While Apple has made eSIMs the standard for U.S. iPhone handsets, the rest of the world typically uses a “dual” setup, allowing both a traditional SIM card and an eSIM to be active simultaneously. WhatsApp’s move may raise awareness of and encourage the use of eSIMs.

Additionally, this change may discourage people from downloading unauthorised WhatsApp-like apps, which are prohibited. Meta, the owner of WhatsApp, emphasised the importance of using the official WhatsApp to ensure message security and privacy.

It’s worth noting that this feature, known as WhatsApp Multiple Accounts, is currently available for Android devices only.

While many see this as a welcome development, some are concerned about the potential misuse of this feature, particularly in relationships.

There are worries that this change could make it easier for individuals to maintain separate WhatsApp accounts for different purposes, such as personal and clandestine communication.

As with most new features, the impact of this change on user behaviour remains to be seen. WhatsApp has encouraged users to use this feature responsibly and avoid downloading unofficial versions of the app to ensure the security and privacy of their messages.

For over a week since Israel’s incessant inhumane attacks against Palestinians intensified, the users of Instagram — Meta’s photo and video sharing app — have raised concerns regarding the big tech company shadowbanning their content and curtailing their freedom of speech, as the world continues to witness human rights violations in Gaza since Hamas — labelled as a “terror organisation” by Western governments — challenged the Benjamin Netanyahu-led government after a surprise attack on October 7.

In the past 11 days, thousands of Palestinians — including over 1,000 children — have been martyred in Israeli airstrikes with its plans to accelerate a ground offensive.

A deadly bombing by Israel, also last night, left an overwhelmingly crowded evangelical hospital in Gaza City destroyed to ashes martyring, at least 500 people in an instant. Hamas’ actions, on the other hand, claimed the lives of around 14,00 Israelis with at least 199 taken as hostages.

Meanwhile, the complaints about pro-Palestine stories and posts on Instagram being shadowbanned came after several users, including influential personalities and content creators with a substantial following as well as those with private accounts, pointed out that the content they are posting on the app is not visible to their followers on the main home feed.

The Cambridge Dictionary described shadow banning as “an act of a social media company limiting who can see someone’s posts (= messages or pictures on social media), usually without the person who has published them knowing.”

Pakistani writer Fatima Bhutto, who is known for being vocal in her support for Palestinians’ right to liberty, said the shadowban seems to be “getting worse”, as she began complaining about issues she has been facing while using the app for the past few days.

“My comments have been locked — only people I follow can post a comment on my page, my views are being restricted as well. My stories and posts are not showing up on people’s feeds,” Fatima told Geo.tv.

Fatima has been consistently indicating about the shadow banning her Instagram account — boasting 111,000 followers — is being subjected to ever since she began posting about Palestinians on her account.

Still being shadowbanned by @instagram who are limiting my comments and story views. I am learning so much about how democracies and big tech work together to suppress information during illegal wars they are unable to manufacture consent for!

— fatima bhutto (@fbhutto) October 16, 2023

“Still being shadowbanned by @instagram who are limiting my comments and story views. I am learning so much about how democracies and big tech work together to suppress information during illegal wars they are unable to manufacture consent for!” she wrote in a post on X, formerly Twitter, on Monday.

Responding to Geo.tv about the relentless censorship by a major social media website, the writer said her users have to manually check for her stories on the Meta-owned platform, whose founder, Adama Moserri, issued a lukewarm statement on the matter, laying bare his apparent bias towards Israel — a regime armed to its teeth against the weaponless civilians in Gaza.

“It’s an insidious form of control — disrupting your ability to communicate because the tech company doesn’t like what you’re saying. All those posting against the genocide unfolding are being shadow-banned, it’s a concerted effort by Meta,” she added.

Censuring US-based tech companies of bias and complicity in war crimes against Palestinians, The Runaways author said: “It is beyond clear that American tech companies don’t actually believe in the values they espouse — freedom of speech, the value of information, and so on — by suppressing voices speaking out against genocide, they are complicit in violence of terrifying proportions.”

‘On wrong side of history’

Usama Khilji, the director of Bolo Bhi — an advocacy forum for digital rights, said there has been deliberate confusion created by conflating Hamas and all Palestinians, which has led to social media platforms of Meta and X censoring posts related to Palestine.

“This is a content moderation crisis where fundamental international human rights law is being violated by social media platforms, and they just be held accountable by users and global civil society,” the digital rights advocate told Geo.tv.

Khilji, when speaking about the ongoing shadowbanning and censorship by Big Tech platforms, insisted that silencing voices against apartheid and genocide means “social media platforms are on the wrong side of history”.

Intent to initiate discourse

Nazuk Iftikhar Rao, a writer based in Lahore, has an audience of over 8,000 followers on Instagram. On most days, Nazuk shares prose, poetry, and creative photography with her thousands of followers.

But as Israel’s war against innocent Gazans broke out, she has been sharing educational and informative content about the ethnic cleansing of this centuries-old Middle Eastern region’s indigenous population. She has also been sharing resources for donating aid for the war-stricken civilians.

“What I started noticing about my engagement on the platform, particularly with posts and stories related to the Palestinian movement, certain key terms like Palestine, Free Palestine, genocide and occupation etc with captions, were being demoted on the Instagram. I noticed this in terms of the likes and visibility on the platform. My friends said they didn’t see the posts and videos about Palestine. This was back in 2021,” she said, speaking with Geo.tv.

Nazuk said her account was initially public and she would get a lot of engagement on photos of books, selfies, and group photos with friends, garnering hundreds of likes and views in a short time. But posts about Palestine that showed information and text blogs would be demoted to 100 or fewer views. “This was even during 2021.”

“Now I’ve noticed that if I post something about Edward Said, it also immediately gets low engagement. The more he entered the mainstream, popular narrative of Palestine, then posts related to his work also became more targeted.”

“About the algorithms, I don’t know how they work. But from my limited understanding, I’ve noticed that ChatGPT and all the other Artificial Intelligence (AI) platforms are being trained on materials that hold the sentiments, opinions, biases, prejudices of a certain demographic, essentially the Global North,” she said.

The writer maintained that the content that automatically aligned with their ideologies and ideas was not targeted.

Sharing her intent behind posting the content, Nazuk said: “My initial intent of posting was to start a discourse. But not just a conversation or educate [people] because I’m also always learning. I noticed that there was a gap between what my friends, particularly from my policy school in the United States, and my friends here were expressing with regards to Palestine and the US policy’s role, and the creation of organisations like Hamas in the vacuum that is left by western imperialism.

“I wanted to bring that conversation into play here, rather than a black and white conversation about Jews vs Muslims or antisemitism vs Islamophobia.”

Nazuk said she aimed to address the void created by misinformation, disinformation, false narratives, and the lack of knowledge and accuracy about historical instances in relation to the ongoing brutalities in Gaza.

“I would bring in poems by Palestinian poets such as Mahmoud Darwish or others. I would try to post their work, opinions, poetries, observations and stories about life under occupation and the so-called ‘conflict’ because it is not essentially one,” she added.

The writer, whose poems and writings have been published in both national and international publications, said in the last year, selective empathy and sympathy were widely observed with regards to who should be rooted for, who has the right to fight back, and the question on whether who is and isn’t a terrorist.

“We’ve seen that in the case of Ukraine and Russia. How there would be articles and detailed photo essays [in publications like] the New Yorker about people fighting occupation by Russians. But similar instances were not been showing up about people of colour or people who did not belong to the Global North or those who were not pre-dominantly white,” Nazuk highlighted.

‘Pepper videos of nature or random pictures in between’

Another Lahore-based writer, Mariam Tareen, said she read a friend’s story about their views drastically falling to single digits, just a few days into sharing information on what was happening in Gaza.

“When I checked my own story views, I saw that I was down to 11 views on all my recent stories. This was down from around 700+ views on my story from the day before,” said Mariam, whose Instagram following exceeds a little over 7,000, while her feed is largely decked with colourful images of books, coffee, and chai (tea).

However, the ongoing episode of horrors in Gaza led the writer to share content on the subject, but she soon noticed a pattern of what appeared like shadowbanning, and she was not the only one to experience this.

“I posted a story sharing what I had noticed, and immediately I got a flurry of messages from people who had experienced the same. It seems many people who were posting in support of Palestine — from public profiles with several thousand followers, to private accounts — were experiencing some form of shadow banning,” Mariam explained to Geo.tv.

But the writer said she tried a few ways to counter this algorithmic censorship imposed by the platform.

“I try to pepper videos of nature or random pictures between stories about Palestine. I tried including a poll in my stories, because I read that if people interact with your stories like answering a poll, or DMing a response, for example, helps get past the algorithm.”

In fact, Mariam added, as a result of the DMs she received after posting about the reduction in her story views, her numbers did suddenly seem to “unlock” and “even my previous stories climbed back up to hundreds of views”.

“Even now, although my views have increased from 11, they are still about a third of what I usually have, and I’ve noticed is that the views increase much slower than before,” she shared.

‘Confusing algorithm, not working anymore’

Hina Ilyas, a digital skills mentor based in Karachi, educates on remote work, and content marketing and shares visuals of her numerous cats on her Instagram platform with an audience of over 1,600. But to keep up with the situation in Gaza, she also engages with and posts pro-Palestinian content. But like most people on the platform these days, Hina, too, is also a victim of shadowbanning.

“It started happening within three to four days of continuously posting stories. I normally get around 500 to 600 views, but lately they are hardly 10 to five. I have lost access to some story editing and media features too and I’m sometimes unable to view other account stories as well,” she said, in communication with Geo.tv.

Hina added this is still happening to her because she is continuously sharing pro-Gaza content and engaging with accounts of Palestinian journalists. She also tried posting random stories to confuse the algorithm, which she thinks isn’t working anymore.

The Karachi-based professional said the responsibility of a platform like Instagram is pretty clear and if they can’t ensure “just reporting” or call out “genocide”, they better shut down their accounts.

“And this responsibility is not just of the big media platform, but equally of the influencer community as well. Sadly, almost all of them are silent at a time when we need to amplify the voices of those reporting on ground in Gaza,” Hina said, calling out the influencer community.

A Karachi-based journalist Aleezeh Fatima said she was posting content on Gaza as someone who had better access to information than a layperson, but she, too, encountered shadowbanning on the Meta-owned company.

“The easier way to raise awareness among people is through our social media including Insta stories and Facebook etc. I was sharing most of the content on Instagram, as I have better reach there. Last week, I realised my normal stories that would get over 1,000 views, but suddenly, they dropped down to just 200. It was shocking because on very bad reach days, I get at least 700 views,” she shared with Geo.tv.

Private accounts also bear the brunt

Meanwhile, a final-year student at the University of Karachi, Hajra, said she has a private account with around 170 followers, but her story views on Instagram have significantly decreased.

“I’m not a celebrity nor do I have the kind of influence that big names may have, so I don’t get why my account became a victim of the ongoing spree of shadowbanning pro-Palestinian content,” she remarked when speaking with Geo.tv.

‘Not deliberately suppressing voice’

Geo.tv also contacted Meta for a comment on the issue, but the company did not share a response, instead, it sent its policy statement on the Mark Zuckerberg-led establishment’s “ongoing efforts regarding the Israel-Hamas war”.

“Our policies are designed to keep people safe on our apps while giving everyone a voice. We apply these policies equally around the world and there is no truth to the suggestion that we are deliberately suppressing voice,” Meta mentioned in its policy statement.

The company, one of the major names in the global Big Tech firms, stated that “content containing praise for Hamas, which is designated by Meta as a Dangerous Organization, or violent and graphic content, for example, is not allowed on our platforms.”

The company said it can make errors and offers an appeals process for people to let them know if they think Meta has “made the wrong decision”, after which they can “look into it”.

Supreme Court annuls trials of civilians in military courts

Sea conditions ‘very high’ as Cyclone Tej moves towards northwestward

IMF condition: ECC set to green light gas tariff hike today

Barwaan Khiladi: Kinza Hashmi discusses her role as Alia

Snap launches tools for parents to monitor teens’ contacts

WATCH: Pakistani traveller deported from Dubai for damaging plane mid-air

Learn First | How to Create Amazon Seller Account in Pakistan – Step by Step

Sajjad Jani Funny Mushaira | Funny Poetry On Cars🚗 | Funny Videos | Sajjad Jani Official Team